by Martin Haffner Associate Editor

The little-known story of how Taiwanese and human rights activists in Japan spoiled a secret agreement with the ROC to deport ‘souvenirs,’ who could have faced execution

Nine Taiwanese nervously stand on an observation platform at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. It’s 9:20am on March 27, 1968, and they are awaiting the arrival of Liu Wen-ching (柳文卿), who is about to be deported back to Taiwan where he faces possible execution for his independence activities. As he is removed from a minibus, a tenth activist, Dai Tian-chao (戴天昭), jumps out of his hiding place and attacks the immigration officials — the nine other activists in tow — while urging Liu to make a run for it. But he’s pinned to the ground.

Amid the commotion, Liu tries to bite off his tongue. As he’s dragged onto the plane, blood gushing from his mouth, he shouts: “Taiwan seinen banzai!” (Long live the youth of Taiwan!). Upon landing at Taipei’s Songshan Airport, Liu is promptly imprisoned, while the 10 independence activists who tried to free him are detained by the police in Tokyo.

The next day, Japanese intellectuals denounce Liu’s deportation as illegal and demand the release of the 10 detainees. Liu’s deportation becomes national news in Japan.

Woodcut The Terrible Inspection by Huang Jung-tsan in Taipei, 1947, depicting ROC military police shooting and beating Taiwanese bystanders.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

What follows is the story of the aftermath of Liu’s deportation, the events leading up to it and a secret agreement between Japan and the Republic of China (ROC) that would have allowed the growing Taiwanese independence movement, centered in Japan, to be crushed.

Since the Taiwan independence movement questioned the legitimacy of the ROC government, captured activists were often court-martialed and given the death penalty or long prison sentences, making the secret agreement a significant part of the shared history of Taiwan and Japan. However, only a small number of files related to it are currently accessible.

Given that Taiwan’s current government is committed to transitional justice, it should encourage its Japanese counterparts to make these files, including those of the Immigration Bureau and Police Foreign Affairs Division, available to the public.

Members of the Taiwan Youth League for Independence are pictured in Tokyo in 1968. Dai Tian-chao is sitting in the front row, far right, Lin Chi-hsu front row, second left, and Chang Jung-kuei is in the back row, second right.

Photo courtesy of World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI)

HUMAN ‘SOUVENIRS’

Events leading up to the incident began with the arrest of Lin Chi-hsu (林啟旭) and Chang Jung-kuei (張榮魁) on Aug. 25, 1967 on the grounds they possessed invalid documents because the ROC refused to renew their passports. Both were leading members of the Taiwan Youth League for Independence (台灣青年獨立聯盟), then the world’s most important Taiwanese independence organization and a predecessor of today’s World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI, 台灣獨立建國聯盟). Taipei wanted them repatriated.

In reality, according to a letter from the Japanese embassy in Taipei, these independence activists served as “souvenirs” that Japanese prime minister Sato Eisaku could present to the Republic of China (ROC) in the lead up to a visit the following month. The pair were soon released after fighting their detention in court.

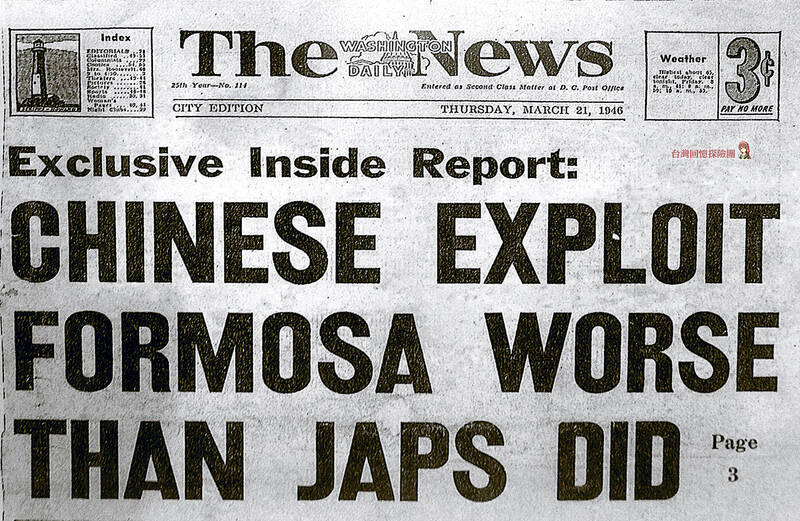

A March 21, 1946 headline for the Washington Daily News.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A second attempt to send a human souvenir to Taiwan occurred when soon-to-be president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) visit to Japan ended on Dec. 2, 1967. This time, it was successful because officials side-stepped the usual legal procedures.

Kuo Hsi-lin (郭錫麟) was arrested that same day and deported to Taiwan before he could seek legal intervention. While deportation usually took weeks, the 24-hour process — applied for the first time ever to Kuo — was later only used for suspected Taiwan independence activists.

Nakagawa Susumu, the then-immigration bureau chief, admitted as much during a hearing in the Japanese parliament on March 29, 1968, when he said that the procedure was implemented after the failed deportation of Lin and Chang and was designed to prevent judicial interference.

A demonstration held by members of the Taiwan Youth League for Independence in remembrance of the 2-28 incident, likely taken in Tokyo circa 1967.

Photo courtesy of WUFI

Kuo’s deportation had a domino effect. Shortly after his return to Taiwan, 15 Taiwanese, including legislator Lin Shui-chuan (林水泉) and University of Tokyo students Liu Chia-chin (劉佳欽) and Yan Yin-mo (顏尹謨), were tried for ties to him and other Taiwan independence activists. The Japanese Embassy in Taiwan warned that the activists could be sentenced to death, as noted in a report from Jan. 8, but the Japanese government still chose to go along with forcibly repatriating more opposition activists.

QUID PRO QUO

Two memos I have found in the Diplomatic Archives in Tokyo (file 2015-1638) reveal that on Jan. 11, 1968, Japan’s Immigration Bureau and the ROC embassy agreed to deport one Taiwan independence activist to Taiwan every month starting in February 1968.

Japanese Foreign Ministry officials had long sought to deport these activists, but were constrained by legal concerns. However, they chose to ignore these reservations when the ROC agreed to accept around 200 Taiwanese and Chinese detained in Japan for crimes like drug trafficking in exchange for Taiwan independence activists. Japan then aimed to deport 40 to 50 of these individuals for alleged visa violations, which would effectively decapitate the movement.

Liu had been living in Japan since 1962 and had become a leading member of the movement. He lived with his common-law partner, Kono Mitsuyo, whom he couldn’t marry because Taipei had stopped issuing him documents.

Hours after Liu’s arrest in March 1968, authorities notified his lawyer that he was going to be deported. After his lawyer was turned away at the immigration office, the Taiwan Youth League for Independence called an emergency meeting after which they convinced Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) parliament member Mizuno Kiyoshi to intervene on their behalf with Nakagawa, who eventually said that Liu would be deported at 9:20am the next day.

With no time to appeal, the activists decided that they would ram the vehicle transporting Liu to the airport and in the process buy time for legal intervention — halting, perhaps permanently, his extradition. But when the activists arrived at the immigration center, Liu was nowhere to be found.

Meanwhile, a second group of activists had been dispatched to a detention center in Yokohama, which is in fact where he was. As the activists arrived at the airport at the same time as the vehicle carrying Liu, his lawyers filed a lawsuit challenging the deportation. Despite a court request at 9am to delay the deportation, immigration officials proceeded. By the time the court officially issued a stop order at 10:20am, Liu was already on the plane to Taipei.

AFTERMATH

This episode and its fallout had an enormous impact on Japanese politics and diplomacy. Nakagawa suggested to parliament ways to reform immigration laws, which would have limited the legal rights of the courts and foreigners. They were rejected and the Japanese government stopped implementing the secret agreement.

In 1970, Taiwan independence activist and Haneda airport detainee Munakata Takayuki, along with Kawata Yasuyo and Inomata Kozo — who were involved in fighting for the rights of other Taiwanese and Korean asylum seekers — founded Amnesty International Japan, the country’s first permanent NGO advocating for foreigner’s rights and highlighting the fate of Taiwan’s political prisoners.

A Tokyo District Court judge would later award Liu’s family two million yen in damages, but the decision was later overturned.

Liu was imprisoned as soon as he arrived in Taipei, but was released two days later. Back in Japan, the other 10 detainees were released after three days. Liu’s wife moved to Taiwan to join her husband, living a relatively normal life under police surveillance.

Lin and Chang won their 1967 lawsuit in the Tokyo District Court in 1971, marking the first successful political asylum court case in Japan. However, Japan would not establish a formal asylum application process until a decade later.

The deportation of Liu and other Taiwan independence activists serves as a stark reminder of how governments can trample on individual rights in order to achieve short term political goals, but also how resilience and opposition on the ground and inside the legal system can lay the groundwork for positive change.

Processing this dark episode in the shared history of Taiwan and Japan can benefit both peoples and governments. It dispels the myth that the Taiwan independence movement was somehow invented by Japanese imperialists and government officials that is propagated by pro-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpieces, while highlighting the contributions of Taiwanese to modern Japan’s society and legal system.

The little-known story of how Taiwanese and human rights activists in Japan spoiled a secret agreement with the ROC to deport ‘souvenirs,’ who could have faced execution.

Nine Taiwanese nervously stand on an observation platform at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. It’s 9:20am on March 27, 1968, and they are awaiting the arrival of Liu Wen-ching (柳文卿), who is about to be deported back to Taiwan where he faces possible execution for his independence activities. As he is removed from a minibus, a tenth activist, Dai Tian-chao (戴天昭), jumps out of his hiding place and attacks the immigration officials — the nine other activists in tow — while urging Liu to make a run for it. But he’s pinned to the ground.

Amid the commotion, Liu tries to bite off his tongue. As he’s dragged onto the plane, blood gushing from his mouth, he shouts: “Taiwan seinen banzai!” (Long live the youth of Taiwan!). Upon landing at Taipei’s Songshan Airport, Liu is promptly imprisoned, while the 10 independence activists who tried to free him are detained by the police in Tokyo.

The next day, Japanese intellectuals denounce Liu’s deportation as illegal and demand the release of the 10 detainees. Liu’s deportation becomes national news in Japan.

What follows is the story of the aftermath of Liu’s deportation, the events leading up to it and a secret agreement between Japan and the Republic of China (ROC) that would have allowed the growing Taiwanese independence movement, centered in Japan, to be crushed.

Since the Taiwan independence movement questioned the legitimacy of the ROC government, captured activists were often court-martialed and given the death penalty or long prison sentences, making the secret agreement a significant part of the shared history of Taiwan and Japan. However, only a small number of files related to it are currently accessible.

Given that Taiwan’s current government is committed to transitional justice, it should encourage its Japanese counterparts to make these files, including those of the Immigration Bureau and Police Foreign Affairs Division, available to the public.

HUMAN ‘SOUVENIRS’

Events leading up to the incident began with the arrest of Lin Chi-hsu (林啟旭) and Chang Jung-kuei (張榮魁) on Aug. 25, 1967 on the grounds they possessed invalid documents because the ROC refused to renew their passports. Both were leading members of the Taiwan Youth League for Independence (台灣青年獨立聯盟), then the world’s most important Taiwanese independence organization and a predecessor of today’s World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI, 台灣獨立建國聯盟). Taipei wanted them repatriated.

In reality, according to a letter from the Japanese embassy in Taipei, these independence activists served as “souvenirs” that Japanese prime minister Sato Eisaku could present to the Republic of China (ROC) in the lead up to a visit the following month. The pair were soon released after fighting their detention in court.

A second attempt to send a human souvenir to Taiwan occurred when soon-to-be president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) visit to Japan ended on Dec. 2, 1967. This time, it was successful because officials side-stepped the usual legal procedures.

Kuo Hsi-lin (郭錫麟) was arrested that same day and deported to Taiwan before he could seek legal intervention. While deportation usually took weeks, the 24-hour process — applied for the first time ever to Kuo — was later only used for suspected Taiwan independence activists.

Nakagawa Susumu, the then-immigration bureau chief, admitted as much during a hearing in the Japanese parliament on March 29, 1968, when he said that the procedure was implemented after the failed deportation of Lin and Chang and was designed to prevent judicial interference.

Kuo’s deportation had a domino effect. Shortly after his return to Taiwan, 15 Taiwanese, including legislator Lin Shui-chuan (林水泉) and University of Tokyo students Liu Chia-chin (劉佳欽) and Yan Yin-mo (顏尹謨), were tried for ties to him and other Taiwan independence activists. The Japanese Embassy in Taiwan warned that the activists could be sentenced to death, as noted in a report from Jan. 8, but the Japanese government still chose to go along with forcibly repatriating more opposition activists.

QUID PRO QUO

Two memos I have found in the Diplomatic Archives in Tokyo (file 2015-1638) reveal that on Jan. 11, 1968, Japan’s Immigration Bureau and the ROC embassy agreed to deport one Taiwan independence activist to Taiwan every month starting in February 1968.

Japanese Foreign Ministry officials had long sought to deport these activists, but were constrained by legal concerns. However, they chose to ignore these reservations when the ROC agreed to accept around 200 Taiwanese and Chinese detained in Japan for crimes like drug trafficking in exchange for Taiwan independence activists. Japan then aimed to deport 40 to 50 of these individuals for alleged visa violations, which would effectively decapitate the movement.

Liu had been living in Japan since 1962 and had become a leading member of the movement. He lived with his common-law partner, Kono Mitsuyo, whom he couldn’t marry because Taipei had stopped issuing him documents.

Hours after Liu’s arrest in March 1968, authorities notified his lawyer that he was going to be deported. After his lawyer was turned away at the immigration office, the Taiwan Youth League for Independence called an emergency meeting after which they convinced Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) parliament member Mizuno Kiyoshi to intervene on their behalf with Nakagawa, who eventually said that Liu would be deported at 9:20am the next day.

With no time to appeal, the activists decided that they would ram the vehicle transporting Liu to the airport and in the process buy time for legal intervention — halting, perhaps permanently, his extradition. But when the activists arrived at the immigration center, Liu was nowhere to be found.

Meanwhile, a second group of activists had been dispatched to a detention center in Yokohama, which is in fact where he was. As the activists arrived at the airport at the same time as the vehicle carrying Liu, his lawyers filed a lawsuit challenging the deportation. Despite a court request at 9am to delay the deportation, immigration officials proceeded. By the time the court officially issued a stop order at 10:20am, Liu was already on the plane to Taipei.

AFTERMATH

This episode and its fallout had an enormous impact on Japanese politics and diplomacy. Nakagawa suggested to parliament ways to reform immigration laws, which would have limited the legal rights of the courts and foreigners. They were rejected and the Japanese government stopped implementing the secret agreement.

In 1970, Taiwan independence activist and Haneda airport detainee Munakata Takayuki, along with Kawata Yasuyo and Inomata Kozo — who were involved in fighting for the rights of other Taiwanese and Korean asylum seekers — founded Amnesty International Japan, the country’s first permanent NGO advocating for foreigner’s rights and highlighting the fate of Taiwan’s political prisoners.

A Tokyo District Court judge would later award Liu’s family two million yen in damages, but the decision was later overturned.

Liu was imprisoned as soon as he arrived in Taipei, but was released two days later. Back in Japan, the other 10 detainees were released after three days. Liu’s wife moved to Taiwan to join her husband, living a relatively normal life under police surveillance.

Lin and Chang won their 1967 lawsuit in the Tokyo District Court in 1971, marking the first successful political asylum court case in Japan. However, Japan would not establish a formal asylum application process until a decade later.

The deportation of Liu and other Taiwan independence activists serves as a stark reminder of how governments can trample on individual rights in order to achieve short term political goals, but also how resilience and opposition on the ground and inside the legal system can lay the groundwork for positive change.

Processing this dark episode in the shared history of Taiwan and Japan can benefit both peoples and governments. It dispels the myth that the Taiwan independence movement was somehow invented by Japanese imperialists and government officials that is propagated by pro-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpieces, while highlighting the contributions of Taiwanese to modern Japan’s society and legal system.